Our Kind of September

- September 13, 2021 08:33

FEU Advocate

September 23, 2024 16:42

By Eunhice Corpuz

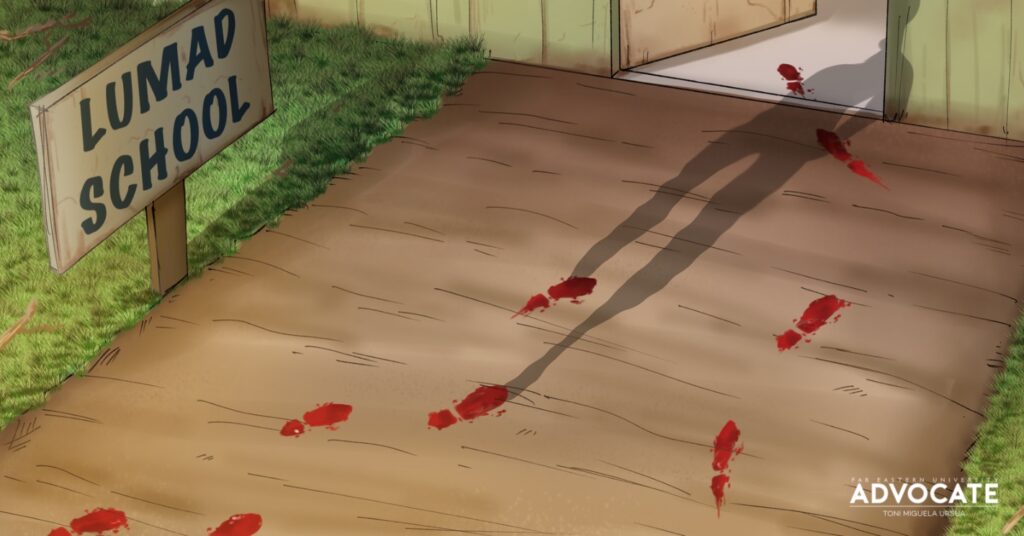

When the crops of knowledge begin to sprout in a muddy, dense, and sloppy track, the Lumad community starts to bear the hunger of fighting for their rights. Amid red-tagging, militarization, and harassment, they depict one’s courage to attain proper education, since for them, a grip of cognizance is their sovereign weapon to protect their ancestral lands.

For the past few years, the Lumad community has been deprived of their basic rights to equality, equity, and education. They face persecution in exchange for their ancestral land.

Once upon a time, there was hope named “Mayka”

In a society where one is marginalized, attaining basic commodities such as food, shelter, and education has now become a privilege difficult to reach.

Lumads are the indigenous tribes from the southern part of the Mindanao island. They are among the poorest of the poor, making it hard to strive for progress and development. Hence, some people contribute to bearing the torch of hope for them.

Micah Simon or ‘Teacher Mayka’ is one of the volunteer teachers who raised the torch of hope in the Lumad community.

Although the first week of her stay was challenging, she asserts that it was fulfilling since the Lumad’s lifestyle differs from what she is accustomed to—it’s simple living.

“S’yempre, una, [noong] first na dating ko [sa komunidad], naninibago ako. Personally, parang una may language barrier kasi nung time na ‘yon hindi pa ako marunong mag[salita ng] Bisaya, natuto lang ako after two weeks. We also have [a] cultural barrier, so itong mga ‘to, noong mga unang linggo, medyo challenging siya talaga for me (Of course, when I first came to the community, I was not familiar with it. Personally, it seems like there was a language barrier at first because, at that time, I didn't know how to speak Bisaya; I only learned it after two weeks. We also have a cultural barrier, so these things during the first weeks were quite challenging for me),” Teacher Mayka shared in an interview with FEU Advocate.

Teacher Mayka also mentions that the Lumad school is structured as a dormitory, allowing her to be with the community all day. Besides, she describes her role as a teacher as more than that; she acts as a mother to the Lumad kids.

“Maagang gigising, sabay-sabay kakain, tapos mayroon kaming tinatawag na ‘tasking.’ Kunwari sa isang room, ‘yung isang group, sila ‘yung maglilinis, tapos ‘yung isang group, sila ‘yung magluluto. So parang andu’n ‘yung kolektibong pamumuhay, the collective living of the community, it is about how you o paano ka nakikipamuhay du’n sa [komunidad] (Waking up early, eating together, then we have something called ‘tasking.’ For example, in a room, one group will clean, then another will cook. So, there’s the collective living where it’s about how you live there in the community),” she narrated.

The tribe learns in two places: Lumad school is established inside their community, while the other, Bakwit school, is located outside and used as their refuge from the threats of militarization.

Typical Lumad and Bakwit schools are the same as Department of Education-accredited schools, only it varies on what it focuses on. For the two schools, Lumad’s main focal point is to teach the culture and agriculture of the tribe.

Meanwhile, the kids in the group were also fond of playing sports just like the other kids who enjoyed their youth.

“Bukod du’n sa pagsasaka, s’yempre mahilig din ‘yung mga Lumad kids [sa] sports, mahilig silang maglaro ng volleyball [at] badminton (Aside from farming, Lumad kids are also shows interest to sports, they like playing volleyball and badminton),” she proudly recounted.

Aside from sports, the Lumad kids teach the volunteer teachers their culture in return, such as crafting beaded bracelets and earrings, during their free time.

Thus, this simple lifestyle is struggling to maintain as the continuous series of red-tagging and threats of militarization begins.

Was there hope?

The progress and development between the two hierarchies of society—the deprived and the privileged—entail a different pathway to interpret.

Simon disclosed that the reason why her supposed two-month stay to teach the community was shortened was because of militarization, where military forces camped on the community.

“At kung nasaan ang Lumad school, nandoon kasi ‘yung mga community, kung nasaan ang community, andu’n ‘yung ancestral land, kung nasaan ang ancestral land, andu’n ‘yung yamang mineral (And where the Lumad school is, there are the communities; when there is a community, there is the ancestral land; when there is ancestral land there are mineral resources.),” she explained.

Simon contends that it is not unbeknown to us that Mindanao is rich in mineral resources, which is why mining and logging companies are trying to enter the Lumads’ domains. These companies showcase their goal of “development” and “progress” by trespassing on these lands.

However, it is the opposite of what the Lumad community believes since, for them, true development is determined by defending the environment and their ancestral lands.

“Dati kasi, kung babalikan natin ang kasaysayan noong wala pang Lumad school, deprived of basic social services such as education at health ‘yung mga Lumad and generally, ‘yung mga katutubo dito sa Pilipinas (If we look back in history when there were no Lumad schools, generally including the Lumads, the natives here in the country were deprived of basic social services such as education and health),” Teacher Mayka pointed out.

The reason indigenous groups face inequalities is because they lack proper education, which creates opportunities for companies to invade their property.

Then, the start of calling for action was prompted by the Lumad asking the government to help them with this matter; however, concrete plans are still nowhere to be found.

The end? THE End.

Becoming a volunteer-teacher is not a sudden feeling of commitment; it is a “What if?” question that became a reality. For Teacher Mayka, teaching the Lumad community was her calling as when she was in high school, she looked up to ‘Teacher Annie.’

“Noong High School ako parang may napanood ako na documentary sa I-witness [at siya ay] is teacher Annie at isa sa mga pinangarap ko [ang] maging isang teacher sa malalayong community. [At] nakilala ko ‘yung mga Lumad noong 2015 [nang] pumunta sila sa UP [University of the Philippines] Diliman (When I was in high school, I watched a documentary on I-witness about Teacher Annie and one of my dreams was to become a teacher in remote communities and then, I met the Lumads in 2015 when they went to UP Diliman),” she narrated.

After two years of meeting them at UP Diliman, she revealed that it gave her life a path to take. Alongside this trail, she met the late Chad Booc, one of the reasons why she persisted in teaching the Lumads.

She and Booc became friends, but he became one of the victims of red-tagging and killings in the New Bataan 5 massacre. Aside from losing a friend, one of her most challenging setbacks was experiencing firsthand red-tagging and threats.

Simon narrated that she was alleged to be a supplier of the armed far-leftist organization New People’s Army at a checkpoint—where she was threatened with a gun pointed at both the sides of her head and one on her lower side, saying that if she was dispatched, no one would know.

It was her first year of teaching when it occurred, but it did not stop her from serving the Lumad community for she firmly believes that as long as there is a native child who wants to learn, she will continuously teach and serve the indigenous community.

Soon after years of service, Simon’s path of teaching the Lumad community ceased when the 200 Lumad schools, including the Bakwit schools, were closed down during the Duterte administration. Out of 200, the 55 schools were ordered and forced to close by the Department of Education Davao Region.

Nevertheless, this does not end the fight to reclaim and protect the Lumad’s ancestral lands and other natives. As long as their presence and calls are recurring, the fight will continue until they receive their well-deserved entitlement: a peaceful abode where no blood should be shed.

Education is a prized possession for everyone; it is an intangible gem no one can snatch from you. This goes the same for the Lumad community; the minerals in their ancestral land are as valuable as their desire for education. Every muddy, dense, and sloppy track they took in pursuit of knowledge was a witness to their steadfast and unwavering passion and dedication to defend what is theirs—then, now, and forever: the right to adequate education and a peaceful, safe shelter.

(Illustration by Toni Miguela Ursua/FEU Advocate)