CHED praises UAAP bubble setup

- April 25, 2022 16:13

FEU Advocate

September 18, 2025 17:01

By Julienne G. Tan

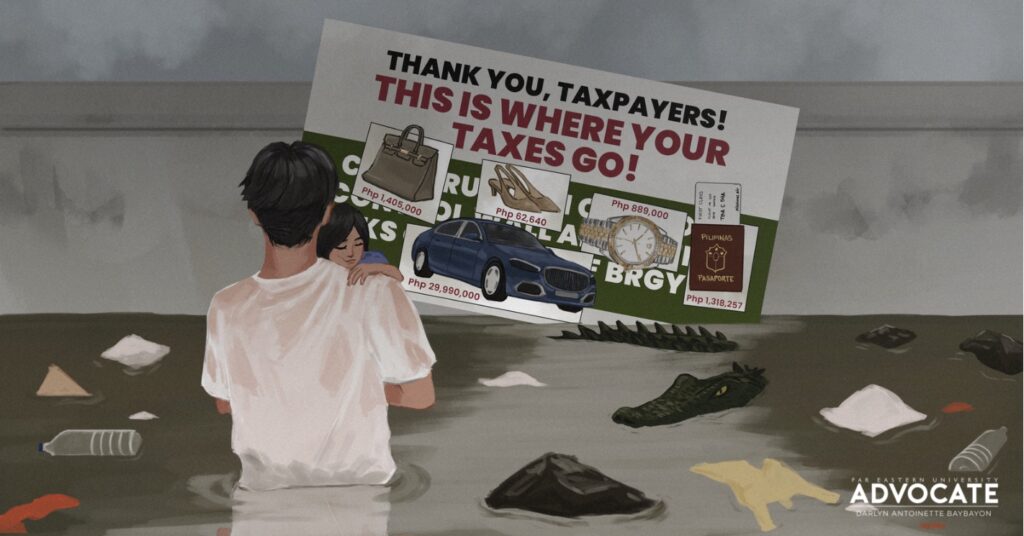

Overnight, Morayta and España Boulevard were submerged in knee-deep waters following the recent monsoon rains in Metro Manila and other cities in Luzon, and students scrambled to keep their books and uniforms dry. For ordinary Filipinos, floods mean disruption and loss, but for the privileged, they are no more than scenery outside their condo windows. Such is the advantage of being a ‘nepo baby’—a child of privilege that inherits not just wealth, but the luxury of staying dry through storms.

This contrast is not just cruel but as real as it is systemic. Despite billions being funneled into flood control year after year, streets continue to become submerged. According to a preliminary Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) report, about ₱545 billion was allocated to flood control projects nationwide since July 2022.

To grasp the scale, that amount could have built hundreds of thousands of classrooms, dozens of major public hospitals, or entire communities of socialized housing for families displaced by floods. Instead, the money is drained through controlled bids and recycled contractors, corruption that does not just siphon funds but ensures broken systems stay broken.

A 2021 Department of Justice report revealed that the DPWH and local government units (LGUs) received the highest number of corruption complaints among government agencies.

Among the names that emerged in the investigations are Cezarah Rowena ‘Sarah’ Discaya and her husband Pacifico ‘Curlee’ Discaya, who control two of the top 15 contractor companies that cornered 20 percent of the ₱545-billion flood control budget since 2022.

But it was not just high numbers; it was a sham competition, flaunted by a garage of 30 luxury cars. The Bureau of Customs later disclosed that eight of those vehicles were smuggled, with another seven lacking Certificates of Payment and showing tax deficiencies, placing the couple’s fortune under scrutiny.

One striking case was their St. Timothy Construction Corp., which ranked third among the top 15 contractors and was tasked to repair the Navotas floodgates in 2024. The gates were damaged after being hit by a vessel, but repairs were delayed for over a year.

When Super Typhoon Carina struck in mid-2025, the weakened structure failed, leaving Navotas vulnerable to severe flooding amid heavy rains in June. Thousands of residents in the city as well as citizens from Caloocan and Malabon were displaced as a result of the destruction that came from the floods.

These are not mere lapses or oversights, but built-in features of a corrupt system: the House of Representatives approves the budgets, the LGUs release contracts, and the DPWH signs off, even when projects are delayed, substandard, or never materialize. Money flows, projects vanish or fail, and accountability is nowhere in sight.

Each stalled project and half-dug drainage canal is a billboard that says “Your taxes are not funding flood walls.” They are building the dynasty heirs’ sports utility vehicles (SUV), designer wardrobes, and lavish vacations. While ordinary Filipinos carry their children through murky water, the taxpayers’ money carries these ‘nepo babies’ through comfort despite the rain.

So if anyone wishes to live a life where their shoes remain dry no matter how high the waters rise while everyone else goes under, here is a four-step guide to navigating the flood season—drawn from the privileges often seen in taxpayer-funded children.

1. Inherit a flood-free lifestyle

In the Philippines, floodwaters do not rise equally. While most commuters roll up their pants, wear their tsinelas, and carry their bags over their heads, some families are spared from the drowned streets altogether as they ride through the rain in their SUVs and seek shelter in their condominiums. The system keeps them dry, not because of better drainage, but because of birthright.

The name Elizaldy Co, representative for the Ako Bicol Partylist in the House of Representatives of the Philippines, former Chair of the House Committee on Appropriations, and co-founder of Hi-Tone Construction and Development Corp., as well as Noel Cruz, owner of Sto. Cristo Construction and Trading Incorporation, are stamped on the same public works budgets that promised flood control, yet delivered substandard and abandoned projects. But their children live far from these failures.

For Claudine Co, daughter of Elizaldy, ₱545 billion in drainage funds has not kept the streets from going under—but it has bought her another Dior tote and a weekend abroad. Her social media, especially her Instagram stories, serve less as personal updates and more as a running log of indulgence: designer goods, travel, and luxury, an online diary that showcases how she is privileged to be shielded from the very problems taxpayers are forced to endure.

The same goes for Jammy Cruz who is known for owning a collection of designer bags and a luxury car, all given by her father, Noel, whose firm has been tied to kickbacks, securing 45 flood control contracts, with a combined estimated value of ₱3.5 billion from 2022 to 2024, according to the DPWH and the Office of the President.

In this country, protection against floods is not built by engineers but inherited through your last name. As taxpayers brace for the next downpour, these heirs remain dry, untouched by waters that sink everyone else.

But for some, their privilege is not just inherited—it is renewed election after election, as taxpayers themselves repeatedly return these heirs’ parents into power.

These nepo babies do not worry about flooded streets. Their only problems are whether or not they are getting traction on their posts, where swollen rivers and submerged streets become content, not catastrophe.

2. Establish your social media presence

In a country where rainstorms can drown communities due to failed flood control projects, residents of cities like Biñan, Laguna often face submerged streets whenever it rains. Yet on social media, none of this tragedy makes an appearance.

Angela ‘Gela’ Alonte is a prime example of ignorance due to privilege. A content creator, an actress, and the daughter of Biñan mayor Angelo ‘Gel’ Belizario Alonte, she is also part of a family long entrenched in politics, carrying their dynasty’s weight as easily as her own fame.

While residents blame her family’s projects for drainage that fails with every downpour, her social media feed tells a different story. It is filled with concerts, travel highlights, and polished OOTDs—far removed from the flooded streets just beyond her phone camera.

When questioned about her ties to a political dynasty back in 2024, she did not confront the critique. Instead, she laughed it off, jokingly calling the comment ‘controversial,’ and turning it into a punchline rather than addressing valid criticism.

With the video resurfacing, this remark has provoked public outcry and discussions online. It was seen as out of touch and insensitive considering the people of Biñan still grapple with flood-prone streets and the lack of proper flood control in their city.

The message is clear: privilege is easier to joke about than to justify, especially when likes and comments drown out criticism.

Meanwhile, former Biñan officials pour P50 to P100 million annually into flood-related damages in just two barangays—but every downpour still leaves streets submerged, despite this large budget.

But online, privilege is repackaged as effortless success, polished reels, and getaways that drown out stalled flood projects. The sleeker the feed, the harder it is to reconcile privilege with accountability.

What makes the situation more concerning is that the danger does not disappear; it lingers beneath the surface. For decades, Biñan’s floods have been met with band-aid solutions, like relief operations that help in the short term but never solve the root problem. With long-term solutions still lacking, residents continue to adjust to recurring floods and cope with the minimum support available as the cycle persists.

In that world, fame drowns out questions, and wealth is not hidden—it is celebrated. It is not the flooded streets that capture attention, but the polished lifestyles that float above them.

3. Let the system work for you

For political nepo babies, public money does not just vanish; it transforms. What should have been poured into flood control projects becomes the ticket to leisure, with an allocation for ‘personal needs’ slipped into every budget hearing.

In theory, these projects go through the DPWH: funds are allocated, local officials award contracts through biddings, and public works agencies are tasked with delivering sturdier roads, clearer canals, and functional drainage.

In practice, much of it drowns in kickbacks, ghost projects, and overpriced contracts handed to known contractors.

Sarah Discaya, who also owns construction firm Alpha & Omega Gen. Contractor & Development Corp., which is labeled second among the top contractors for various flood control projects, offers a vivid example.

During a Senate Blue Ribbon hearing investigation on the flood control anomalies, she admitted that nine construction companies she and her husband controlled all bid for the same contracts—effectively guaranteeing one of them would win.

Senator Jose Pimentel ‘Jinggoy’ Estrada pressed her on the scheme, with Discaya responding with uncertainty, him pointing out: “So kahit sino doon, kahit sinong manalo sa bidding na 'yon, ikaw ang panalo. Dahil sa'yo lahat 'yon (So whoever wins in that bidding, you’re still the real winner, because all of it belongs to you).”

The Philippine Contractors Accreditation Board (PCAB) revoked all nine of her firms' licenses, calling their bidding scheme ‘inimical to public interest’ and a violation of procurement laws because it is all under common ownership.

But the sanctions came only after billions in projects had already been awarded. By then, contracts in places like the Tangos-Tanza navigational gate in Navotas and at least seven outgoing Iloilo projects were left hanging, with stalled works worsening the floods residents had long endured. Funds were not back, and accountability stopped at paperwork; the projects remained missing, while the floodwaters stayed unforgiving.

Discaya’s dominance in bidding circles also shows how construction firms often follow a rigged logic: it is less about who can build the strongest dams and more about who can sit closest to power. Their long list of companies did not just win by chance; they reflect a system where business empires and political dynasties intertwine, producing a generation in governance that inherits not just privilege, but entire projects.

When contracts cluster under the same names across administrations, lines are blurred between state infrastructure and family enterprise, leaving citizens to wonder whose interests ‘flood control’ really serves.

4. Secure the next term, keep the cycle flooding

The final move in the dynasty playbook is simple: survival through succession. Families that profit from failed projects do not just cling to power—they multiply it, ensuring no election season passes without their names on the ballot.

In Davao City, the Duterte family has ruled almost uninterrupted for over 30 years. Their grip on power has outlasted mayors, storms, and billions in flood allocations. From 2020 to 2022 alone, the city received ₱51 billion in flood control allocations—but residents still waded through knee-deep water whenever rains came. Drainage projects stalled, waterways clogged, families displaced. Yet election after election, the Duterte name stayed on the ballot, framed as perfect leaders, even if promises dissolved along the floods.

This is how dynasties survive: by turning recurring crises into campaign rituals. Floods become photo ops, disasters become slogans, and power is passed down as casually as property. And it is not just Davao. A 2025 report by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism found that approximately 113 out of 149 mayors hail from political dynasties—families that inherit not just office, but the privilege and profit that come with keeping problems unsolved.

By the time a nepo baby runs for office, the ground to success has already been paved and paid for, with the very money meant to keep roads and canals intact.

The Dutertes’ hold on Davao is a prime example of how political dynasties maintain power even as critical problems persist, sustained by a loyal base that views them as symbols of order and strength.

This is where the debate begins to unfold. Some say heirs should not be singled out online for the failures of their families. But critics counter that in a system where politics functions like a family business, privilege is inherited as much as office itself.

To them, these nepo babies are not passive victims of public anger, but active beneficiaries of a structure that keeps power concentrated while leaving floods—and ordinary citizens—neglected.

In this arrangement, public office is less a calling to serve the masses than a family business. One that thrives precisely because the same problems never get solved. Floods often resurface in campaign speeches, where disasters are reframed as opportunities for propaganda and ribbon-cuttings. For commuters and students, wading through water is a yearly routine, but for political families, ‘managing’ these crises has become their hold on power.

These political dynasties do not just prepare for the next typhoon—they prepare the next candidate, ensuring the storm never ends, no matter how many of their faces have come and gone.

Congratulations, you’re now a taxpayer-funded nepo baby!

What these four steps really expose is not just a guidebook for the privileged, but a mirror of a government that rewards incompetence and shields dynasties from the consequences of failure. As waters keep rising, it is ordinary Filipinos who are left to improvise survival in their homes and streets, abandoned by the very people sworn to protect them.

For those born into power, the cycle is effortless. They inherit not only surnames but also the foundation to stay untouched. Claudine Co, Gela Alonte, and Jammy Cruz have faced public backlash online, with Cruz and Co deactivating their accounts after criticism spread on social media platforms like TikTok and Facebook.

Celebrities who took a stance also surfaced, such as host-actress Bianca Gonzales, calling out the unfairness of such privilege and hoping those who squander public funds on luxuries will one day be held accountable in a post.

But scrutiny often stops at the children, with their curated lives on display, while the parents who hold real power remain insulated. These criticisms barely touch the larger problem, as trends fade, outrage passes, and yet people still suffer, roads still flood, and real change remains out of reach.

Real transformation requires structural reforms: transparency in public spending, accountability for contractors and political families, and a governance system that prioritizes public welfare over inherited privilege. Without these measures, outrage ignites, yet the cycle endures, while ordinary Filipinos are left to face the storms alone.

So, if the dream is to keep your shoes spotless while students wade through España, follow this foolproof four-step guide. This is the blueprint of the taxpayer-funded ‘nepotism babies,’ where comfort is inherited and power is protected through generations. But no matter how high their walls are, they cannot escape this truth: their comfort is built on the sinking of a nation. Every flood is a reminder of the debts that privilege refuses to pay.

(Illustrated by Darlyn Antonette Baybayon/FEU Advocate)