‘Walang mali sa atin:’ FEU alum boosts femme visibility in ‘Sparks Camp’

- June 27, 2024 20:04

FEU Advocate

November 26, 2025 20:46

By Cassandra Luis J. De Leon, Shayne Elizabeth T. Flores, and Julliane Nicole Labinghisa

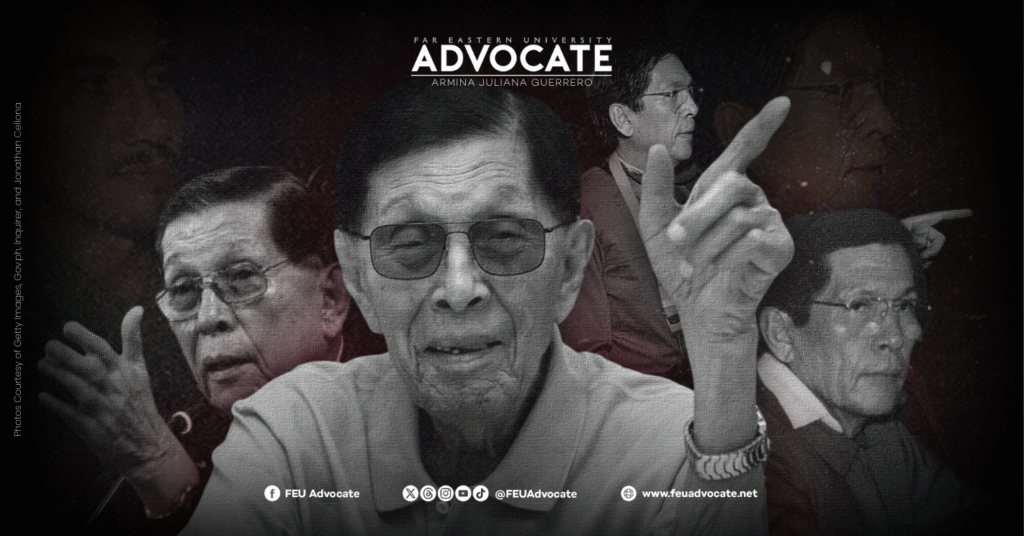

After his death at 101 years old, political figure Juan Ponce Enrile is being honored by many, but the positions he held in the past regimes cast a shadow on the nation’s history. In a country where death often means immediate absolution, and at a time when social media is split between glorifying and condemning him, we must ask: who is really deserving of mourning—an enabler of corruption and oppression, or the people who suffered and are still suffering because of his actions and the twisted system he allowed?

Beginning his political career as the Undersecretary of the Department of Finance in 1966, Enrile quickly rose to power and was able to hold key positions in the government. Over the decades, he served under different administrations, from Ferdinand Marcos Sr. to Ferdinand Marcos Jr., which allowed him to become an influential force in shaping the country’s political landscape.

His ability to align himself with those in power, like when he withdrew his support from the despotic system he was a part of—the Martial Law, and to reinvent his public image enabled him to occupy roles that were contradictory yet helped preserve authority.

In the same year he started, he became the Acting Commissioner of Bureau of Customs, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Philippine National Bank, and Acting Head of the Insurance Commission.

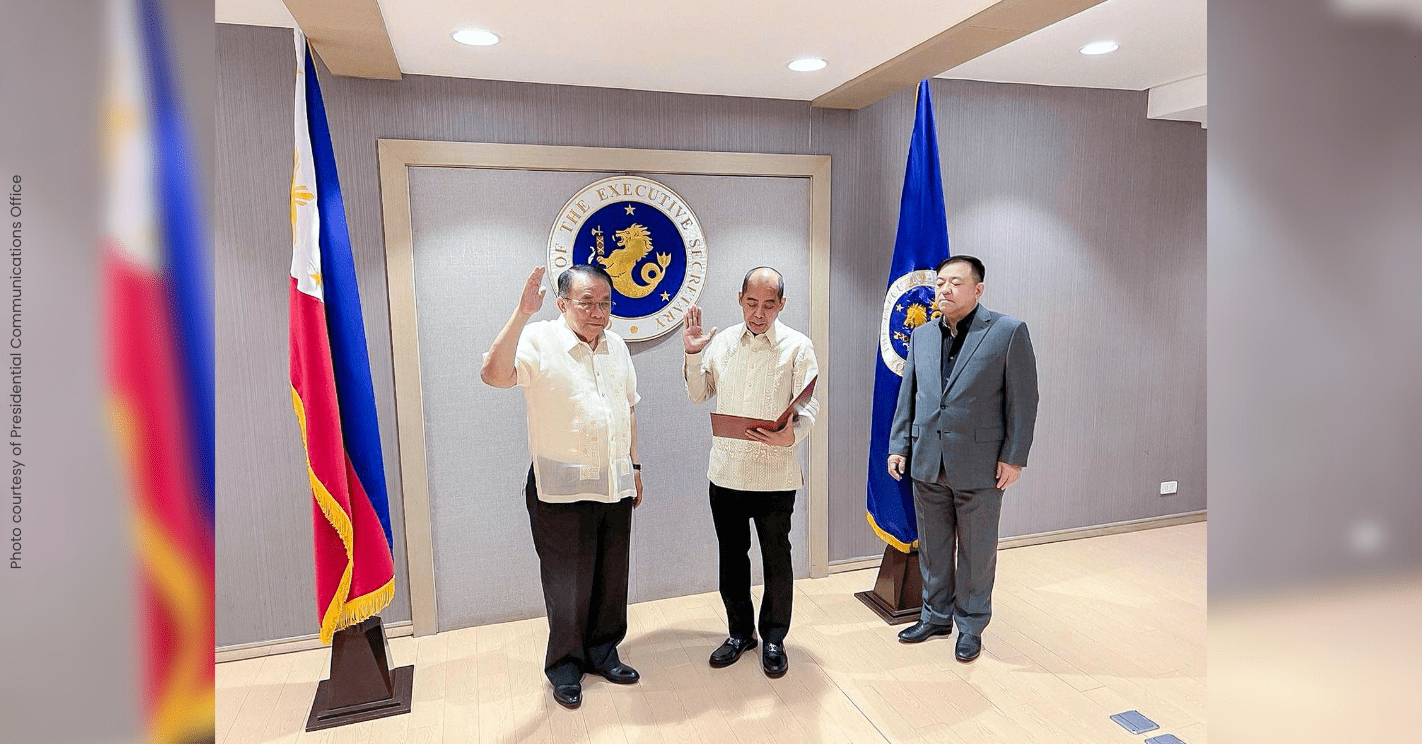

He also served as the Secretary of Justice in 1968, National Defense Minister in 1970, Senate President in 2008, Senator of the Philippines in 1987 to 1992, 1995 to 2001, and 2004 to 2016, and Chief Presidential Legal Counsel in 2022.

With his life remarkably spanning a century, Enrile passed away last November 13.

A force behind Martial Law

Enrile helped administer the Marcos dictatorship, which resulted in human rights violations, with 72,000 imprisoned, 34,000 tortured, and 3,240 killed. Serving as the Secretary of the Department of National Defense from 1970 to 1986 under Marcos Sr., Enrile was one of the “chief architects” who pushed for the declaration and implementation of the 1972 Martial Law.

The so-called chief architect of Martial Law and Minister of National Defense extended Marcos’ mandates, granting Enrile more authority to the military.

To justify the proclamation of Martial Law, an alleged ambush on Enrile took place in Mandaluyong while he was on his way home from a military briefing. This incident strengthened the government’s claim that the country was threatened by terrorism and communism, prompting them to act in “protection of the nation’s security.”

However, Oscar Lopez, whose family previously owned the Manila Chronicle and a resident of the subdivision where the incident took place, stated that their family driver saw that the car was empty after the shooting and nobody was hurt.

In a press conference on February 23, 1986, Enrile and Fidel Ramos admitted that the ambush was staged, but years later, Enrile would contradict this in his own book, claiming that it was his political enemies who spread that the ambush was orchestrated.

With the execution of Martial Law came countless massacres of the Filipino people—one allegedly tied to Enrile himself.

According to investigations, several members of the Special Forces–Integrated Civilian Home Defense Forces (SF-ICHDF) entered Barrio Sag-od in Las Navas, Northern Samar, gathering residents to search for an alleged New People’s Army commander roaming the area in September 1981.

After separating the men from the women and children residents, the SF soldiers forced the latter to march away from the barrio when a burst of gunfire erupted, coming from the direction of the barangay.

The Sag-od Massacre, which resulted in the death of over 45 residents including children, supposedly lasted around 15 minutes.

The soldiers were allegedly allied with the group referred to as the ‘Lost Command,’ a paramilitary group pursuing insurgents. Further investigation also revealed that they doubled as security guards for the San Jose Timber Corporation, which was owned by Enrile.

With the people in EDSA

After years of cruelty during Martial Law, Enrile suddenly became a catalyst of revolution. With his betrayal to Marcos Sr. to become part of a broader mutiny, his immense influence as the Defense Minister further provoked the 1986 People Power Revolution.

As a known friend and ally of Marcos Sr., public momentum shifted when Enrile and then Vice Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines Fidel Ramos publicly announced their withdrawal of support for the dictatorship through a press conference held at Camp Aguinaldo on February 22, 1986.

Through Radio Veritas and the appeal of former Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin to support the betrayal of Enrile and Ramos, the radio became the country’s main communication channel, transmitting information before eventually uniting millions of people to join mobilizations.

As a key figure during the Martial Law era, in some ways, Enrile’s defection was interpreted that even people in power can no longer tolerate the violence and tyranny of the government. However, it may also be his attempt to clear his name and evade scrutiny when it was a system he himself took part of.

The People Power Revolution brought millions of Filipinos to the streets of Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), ultimately dethroning Marcos Sr. and forcing him and his family to exile.

Vote against justice

From the People Power Revolution in 1986 to the Second EDSA People Power Revolution in 2001 that dethroned former President Joseph ‘Erap’ Estrada, Enrile managed to remain relevant and involved in political anomalies.

Prior to the impeachment trial of Estrada in late 2000, thousands of Filipinos had already been marching on the streets to call for his resignation due to bribery and gambling allegations made by then Ilocos Sur Governor Luis ‘Chavit’ Singson, Estrada’s close friend and political ally, in October of 2000.

After a series of protests to hold the corrupt former president accountable, the impeachment trial of Estrada started from December 7, 2000 to January 16, 2001.

Moreover, 21 of the senator judges, which Enrile was a part of, were given the chance to vote on the opening of the second envelope that contained bank documents which would have proved that Estrada received money from bribes and kickbacks during the January 16, 2001 trial.

Among the 21 senators, 11 voted against the opening—including Enrile.

This sparked a massive outrage, fueling the Second EDSA Revolution, with their vote interpreted as a betrayal of public trust, drifting further away from the justice promised.

Role in the pork barrel scam

As if the late politician’s track record could not get any more dreadful, he also had a hand in one of the biggest corruption scandals in the country.

Exposed in 2013, the ‘pork barrel scam’ pertains to the lawmakers’ misuse of the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF), also known as pork barrel.

PDAF is a discretionary fund granted to each member of the Congress, specifically allotted for the government’s priority development projects.

However, instead of being appropriately spent, investigations and numerous pieces of evidence revealed that P10 billion of pork barrel was funneled by lawmakers to ghost projects and fake non-governmental organizations in exchange for massive kickbacks, with Janet Lim-Napoles named as mastermind.

Citing sufficient evidence of his involvement, the Office of the Ombudsman indicted then Senator Enrile, along with other Congress members, with plunder and graft charges in 2014.

Specifically, Enrile was accused of receiving as much as P172.8 million.

While the former senator initially expressed willingness to face the charges against him in respect to due process—even going as far as to claim that he would not ask for special privileges once he is detained—the progress of his case was marked with requests for consideration of his old age and deteriorating health.

Enrile also denied his involvement in the pork barrel scam, insisting that his participation was merely to recommend the projects to be funded under the PDAF.

After a decade of back-to-back investigations and case procedures, Enrile was finally acquitted of his remaining graft charges due to the prosecution’s “failure to prove guilt beyond unreasonable doubt” last October 24.

This was only weeks before his death, allowing the late politician to successfully evade accountability.

With all his sins seemingly forgotten and absolved, Enrile’s death was honored with prestige and dignity as he was laid to rest at the Libingan ng mga Bayani in Taguig City last November 22.

From living through years-long dictatorship, changes in presidency, and various anomalies, to maintaining political relevance even after the generations he has lived, Enrile’s name still echoes both in controversies and grief—stuck in the chambers of the Martial Law legacy, political revisionism, and accountability, which he did not carry into the afterlife.

(Photos courtesy of Getty Images, Gov.PH, and Inquirer; Layout by Armina Juliana Guerrero)