Fire hits UE Manila

- April 02, 2016 16:41

FEU Advocate

November 14, 2025 10:30

By Franzine Aaliyah B. Hicana

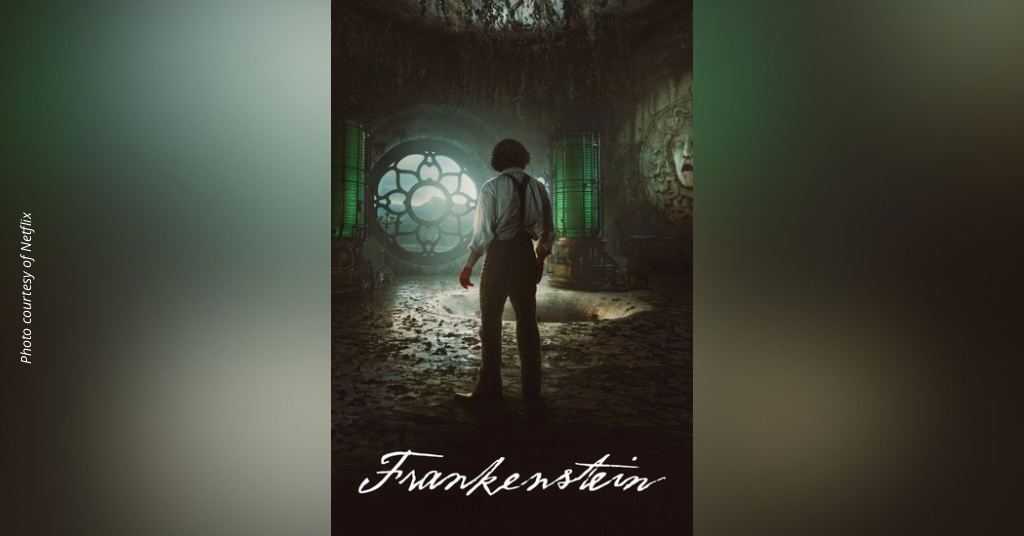

#Refreshments: The dead rise once more, but this time, not by lightning alone. In Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Frankenstein’ (2025), resurrection is an act of arrogance disguised as genius, and love becomes both salvation and a curse. While audiences may expect gothic horror soaked in candlelight and grave soil, what del Toro delivers is far more unsettling: a mirror, held up to humanity’s oldest sin—the desire to be God.

From its first crack of thunder, Frankenstein resurrects Mary Shelley’s timeless fable not as a simple monster story, but as a study of men’s hubris—of ambition that creates but refuses to nurture. Victor Frankenstein (played by Oscar Isaac) is not the madman of legend, but something more frightening: a visionary blinded by his own light.

The God that fails

Victor Frankenstein is the film’s greatest paradox—both the engine of creation and the source of all destruction. In del Toro’s retelling, Victor is not the misunderstood genius audiences might expect, but the embodiment of inherited pain.

Every frame of Isaac’s performance carries the residue of a man raised in cruelty. His father, Leopold Frankenstein (played by Charles Dance), rules over him with emotional distance and contempt, teaching him that affection is conditional and that worth must be proven.

Del Toro situates this trauma at the root of Victor’s ambition. Conquering death becomes an act of rebellion, a twisted declaration of independence. The experiment is no longer about science; it is a child’s desperate plea to be seen.

Here, the film's critique becomes most incisive as Victor's experiments are financed by Heinrich Harlander (played by Christoph Waltz), a war profiteer who embodies the era's toxic male ambition.

Set against the backdrop of industrial and wartime innovation, Harlander’s character exposes how masculinity in the modern age becomes entangled with conquest, capital, and control.

Harlander’s decision to fund Victor’s experiment stems not from the belief in progress but the desire to escape his own syphilis using the Creature’s body as his own. This transforms science into an extension of the male ego, driven by fear of mortality and loss of power.

His desperation matches Victor’s godlike obsession, revealing a toxic masculinity that seeks to dominate life rather than understand it.

From there, del Toro charts Victor’s descent with operatic precision. The camera follows him through war-torn Europe, amid the industrial carnage of the Crimean War, where human bodies are reduced to instruments of the empire.

The alignment of scientific progress with industrialized death turns Victor into a reflection of the world that built him—brilliant, efficient, yet utterly soulless. His laboratory, gleaming with brass and blood, becomes an altar to the same cruelty he once condemned.

When Victor succeeds, the result is not wonder but revulsion. The scene of creation—lit in del Toro’s trademark chiaroscuro, scored with aching strings—is filmed like a birth corrupted by pride.

When the Creature (played by Jacob Elordi) first awakens, Victor’s reaction is not fear but ecstasy. Isaac plays the moment with near-childlike wonder—his voice trembling as he calls the newborn life toward the light. “Look,” he whispers, raising the creature’s face toward the window, “the sun.”

It is a moment of brilliant irony, the word ‘sun’ echoing ‘son,’ a fragile glimpse of the father Victor could have been. For a while, he believes he has transcended death, that creation and possession can coexist. But del Toro refuses sentimentality. The warmth in Victor’s eyes soon curdles into control.

The scene that begins as revelation ends as imprisonment. He chains the Creature in the very place that gave him life, studying him like a specimen, speaking to him like an experiment gone wrong. What might have been affection becomes domination, and the promise of creation collapses into captivity, proof that even Victor’s kindness is another mask for his desire for authority.

Isaac plays him as a man consumed by the need for control. Every act of creation is followed by destruction, every moment of intimacy by withdrawal. He cannot love what he cannot dominate. His pursuit of perfection is a shield against the vulnerability he associates with failure.

The more he tries to prove that he is not his father, the more he becomes him. When the Creature escapes, Victor’s motivation shifts no longer to create, but to punish. His vengeance is personal, almost pathetic: the wounded son chasing his own reflection across frozen wastelands, desperate to erase evidence of his imperfection.

Del Toro’s visual storytelling reinforces Victor’s emotional decay. The warm candlelight of his laboratory gives way to the cold, sterile blue of the Arctic, mirroring the spiritual death that follows his physical success. The final confrontation between creator and creation is staged not as a battle, but as a confession.

A dying Victor, frail and shivering, finally sees the truth he had run from: he was never playing God. He was re-enacting his father’s cruelty, dressing it in the language of discovery.

When the Creature kneels beside him and whispers, “Rest now, Father. Perhaps now, we can both be human,” the film delivers its quiet, devastating catharsis.

Victor Frankenstein is the anti-hero of this tragedy, undone by the same ambition that defined him. Isaac portrays a man who has never known tenderness, whose brilliance isolates and destroys him.

In the end, Frankenstein (2025) is less a monster movie than a requiem for wounded men who mistake control for love. Victor’s tragedy is not that he tried to play God, but that he never learned how to be human.

Del Toro's portrayal of Victor feels urgently modern. Today, scientists, technologists, and inventors build powerful tools like artificial intelligence, genetic editing, and autonomous systems, often without asking what kind of world they are creating.

Like Victor, we chase innovation for pride, profit, or validation, mistaking the allure of progress for purpose. The question is no longer whether we can create life, but whether we can live with what we've made.

Del Toro's version carries that warning into the 21st century, where creators of artificial intelligence, biotech, and digital empires often mirror Victor's blindness.

Like him, they pursue innovation with honorable motives, yet their means turn the enterprise monstrous.

The film becomes a reflection of our own hubris: invention without introspection, progress without empathy.

Born of sin

One of the most striking achievements of del Toro’s Frankenstein is how it repositions the Creature as the emotional and moral center of the story. Contrary to popular misconception, he is not the monster of legend.

He is never given a name, never granted the basic acknowledgment of personhood, and yet he possesses an innate curiosity and capacity for empathy that the humans surrounding him repeatedly disregard.

Del Toro emphasizes that the Creature’s ‘monstrosity’ is not inherent, but the product of his environment: chains, isolation, societal rejection, and the neglect of the very figure who brought him into being. His acts of aggression are not born of evil, but of desperation and existential loneliness, a response to constant misunderstanding and abuse.

Jacob Elordi’s performance captures this duality with nuance. The Creature is physically imposing yet emotionally transparent; every movement, every look conveys both intelligence and vulnerability. When he is met with tenderness from the blind old man, the film underscores his potential for moral and emotional growth.

In reading, speaking, and experiencing compassion firsthand, the Creature embodies how goodness is cultivated, not predetermined by form. Del Toro’s framing of these scenes, often bathed in soft, natural light and contrasted with the harshness of his confinement, reinforces the theme that nurture—or the lack thereof—shapes destiny far more than nature.

Elizabeth Lavenza (played by Mia Goth) is introduced as the fiancé of William Frankenstein (played by Felix Kammerer), Victor’s younger brother, placing her at the heart of the family’s tangled dynamics. Her compassion and kindness extend beyond the humans she loves. She becomes one of the first to recognize the Creature’s sentience, treating him with empathy and care when others respond with fear or cruelty.

Their interactions are tender without being sentimental, emphasizing that the Creature’s capacity for goodness is nurtured through connection, and that emotional recognition from others is essential to his moral and psychological development.

Through Elizabeth, the film showcases that even amidst pervasive cruelty, acts of understanding can profoundly shape a life denied of care.

The film also explores the societal dimension of the Creature’s plight. Villagers attack him, misinterpret his intentions, and view him as an outsider solely because of his appearance. These encounters further illustrate how his monstrosity reflects the world around him rather than any intrinsic trait.

Del Toro visually and narratively ties this to Victor’s failure as a creator: the Creature’s suffering is a direct consequence of parental abandonment. The film repeatedly presents Victor’s cruelty alongside society’s rejection, suggesting that true monstrosity arises not from creation itself, but from the repeated denial of care, understanding, and recognition.

By the time the Creature confronts Victor in the Arctic, he has transformed from victim to moral authority. He articulates his need for acknowledgment and connection, demanding a companion not out of malice, but from an essential, human longing for belonging.

His journey culminates in radical forgiveness, granting Victor mercy in death that he himself was never given at birth. In this act, del Toro elevates the Creature above the traditional role of antagonist. He is the thematic anchor of the film, the living proof that cruelty is learned, and that compassion—even in the face of betrayal—is the true measure of humanity.

Del Toro’s Creature forces us to reconsider who the veritable monster is. His intelligence and empathy stand in stark contrast to Victor’s cruelty, showing how neglect and abandonment breed violence.

Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein from a fractured sense of self, pieced together like her creature.

Del Toro channels that idea into a modern parable about alienation in a fragmented world. Today, we build technologies and social platforms that promise connection but often deepen isolation.

Like the Creature, we navigate systems made by creators who never considered how their inventions might shape or wound those who use them.

The cost of creation

Del Toro’s Frankenstein is a haunting and intricate work. Its dual-perspective structure and non-linear storytelling give the Creature’s experience profound weight, emphasizing the effects of isolation and neglect.

The film reinvents the horror genre, transforming it from a gothic spectacle into a psychological study of human cruelty. Victor’s failures and learned brutality are at the heart of the story, showing that genuine horror comes not from science or monsters, but from the choices of the people who create and abandon.

Del Toro's film becomes a mirror for our age of innovation: an era that moves faster than reflection allows. As scientists and technologists push the boundaries of what can be done, the moral question of what should be done often fades into the background. Like Victor, we risk creating before we comprehend, giving life to forces we may not be ready to guide.

This is why ethical safeguards must remain at the heart of discovery: without them, experimentation for its own sake could lead to another Frankenstein-like tragedy, only on a massive, global scale.

The film stands as both a warning and a reminder to create with conscience and to measure success by responsibility.

By the end, Frankenstein delivers an unforgiving truth: humanity is exposed in what we neglect as much as in what we create. Victor’s brilliance kills because he cannot care; his cruelty is inherited, learned, and repeated. Del Toro shows that power without responsibility is a weapon, and cycles of trauma do not end on their own. Compassion is not a virtue—it is a choice, and failing to choose it is the real monstrosity.

(Photo courtesy of Netflix)