Sinepiyu XV kicks off annual film festival with calls for short film entries

- March 21, 2023 12:55

FEU Advocate

January 20, 2026 19:44

Mirasol

By Franzine Aaliyah B. Hicana, Features Editor

Open TikTok and you will likely run into the ‘factory reset’ trend within minutes. Every video follows the same arc: queerness cast as a phase, a chance meeting with the ‘‘right’’ partner, and a punchline declaring a return to being straight, often set to Moira Dela Torre's ‘Titibo-tibo.’ To some, the joke lands because it leans on an old assumption, one that treats sexual orientation as a temporary detour rather than an identity, erasing queer experiences and reinforcing a regressive, harmful logic.

At first glance, the trend appears harmless, even comedic. Videos joke about ‘resetting’ someone who is gay by pairing them with the ‘‘right’’ opposite-gendered partner, as if sexual orientation were a faulty setting waiting to be restored to default.

But this is not mere satire, nor is it a clever subversion. It is a repackaging of old violence in new digital clothing; conversion therapy logic disguised as humor, made palatable by virality.

Just as conversion therapy promised to “fix” people through counseling, prayer, or coercion, these TikTok videos subtly tell viewers: your identity is wrong until it fits societal expectations.

There is something deeply unsettling about how easily this trend has taken root in Filipino online spaces. It does not exist in a vacuum. It thrives precisely because it echoes beliefs many already hold but rarely interrogate: that heterosexuality is the norm, that queerness is temporary, and that queer identity exists for public commentary and correction.

Scroll through the comment sections, and the mask slips entirely. What begins as ‘jokes’ quickly devolves into something darker.

“Ngayon lang ‘yan.” “Phase lang ‘yan.” “‘Pag naka-meet ng tamang babae/lalaki, babalik din sa normal.”

These are not idle remarks. They are the words of erasure—phrases many of us first heard from older generations when we were younger, used to dismiss our identities as temporary, confused, or correctable.

Now, these same lines are being repeated by a generation that prides itself on openness to all gender expressions and sexualities. It signals not progress, but regression, sliding back into the same bigotry we once named and resisted.

This is how violence operates online—not always through slurs or threats, but through consensus. When thousands repeat the same sentiment, cruelty becomes communal, and dissent feels excessive. In Filipino digital culture, where virality often trumps accountability, the moment an opinion becomes popular is the moment it becomes ‘untouchable.’

Homophobia in Filipino spaces is often framed as something distinctly masculine and overt. Men are typically seen as its main enforcers, policing queer identities through mockery or hostility. This framing, however, is incomplete and too convenient.

In contrast, Filipino women often reproduce the same homophobic logic through softer language. Concern replaces ridicule, morality replaces aggression, and care replaces contempt.

Phrases framed as advice or protection carry the same implication that queerness is something to be corrected or outgrown. The difference lies not in belief, but in delivery.

Taken together, this contrast reveals that homophobia persists not because of gender alone, but because heteronormativity is deeply internalized across it. Whether enforced through mockery or concern, the result is the same. Queer identities are treated as deviations requiring correction.

At its core, the ‘factory reset' trend also reinforces heteronormativity as destiny. It frames straightness not as one orientation among many, but as the final, ‘correct’ outcome. Anything else is treated as a detour—interesting perhaps, but ultimately something to outgrow. The implication is clear: queerness is not an identity, but a malfunction.

This logic is especially apparent toward bisexual and pansexual people, who are often the trend’s targets. The idea that someone ‘just needs to try’ the opposite sex rests on the assumption that attraction must be exclusive to be real.

Bisexuality and pansexuality are flattened into indecision, confusion, or refusal to choose. In a world that already stigmatizes them—from both straight and queer spaces—this trend gives social permission to dismiss their identities entirely.

It is worth saying plainly: while labels can evolve, no one owes that evolution to public pressure. Growth is not something spectators get to demand. When identity changes, it must come from the person themselves, not from coercion disguised as humorous banter.

More troubling still is how the trend blurs the boundaries of consent. The insistence that someone should ‘just try’ the opposite sex mirrors sexual assault-adjacent logic—the idea that desire can be negotiated, overridden, or rectified through exposure. It reduces attraction to experimentation for the comfort of others rather than an expression of the self.

When consent is framed as something flexible, something that can be argued away, the consequences extend far beyond TikTok.

Compounding this harm is the persistent confusion between sexual orientation and gender expression. The trend thrives on stereotypes: feminine men are assumed to desire men; masculine women are assumed to want women. Queerness is reduced to aesthetics, and deviation from gender norms becomes evidence of one’s sexual orientation. In doing so, the trend punishes people not for who they love, but for how they look and behave—teaching viewers to police both.

The impact is not uniform. A young, masculine-presenting woman in a rural town may hear whispers from neighbors, while a feminine man in a conservative household sees his identity mocked online. Virality magnifies existing inequalities.

What makes this particularly dangerous is how normalized it has become. The comments are filled with people emboldened by numbers, convinced that popularity equals truth.

“Marami naman kaming ganito mag-isip.”

But consensus has never been a reliable moral compass. History has proven, time and time again, that majorities are capable of profound harm.

Algorithms do not discern cruelty. They amplify what keeps viewers engaged. Likes, shares, and repeat loops turn subtle erasure into trending content, signaling to millions that marginalizing queer identities is acceptable—or even funny.

To dismiss this trend as just ‘content’ is to ignore how media shapes belief. TikTok does not merely reflect culture; it accelerates it. When millions are exposed to the same joke, framed the same way, reinforced by the same comments, it does not only stay online—it bleeds into classrooms, family gatherings, and policy debates. It becomes common sense.

And common sense, in this case, becomes deeply violent.

Being gay is not something that can be fixed, reversed, or reset. It is not a setting that can be changed once society grows uncomfortable. To suggest otherwise is to invalidate lived experiences and reopen wounds queer Filipinos have spent decades fighting to heal—often in a country that still withholds legal protection, recognition, and safety.

Queerness is not a glitch. It is not an error, a phase, or a setting gone wrong. No one needs to be reset, corrected, or returned to default. There was never anything broken to begin with.

We are living in a time when conversations around gender, sexuality, and consent are finally gaining ground. Yet trends like this push us backward, reasserting the idea that identity is subject to public approval and that deviation from the norm invites correction. They give space to homophobia and misogyny under the guise of humor.

The media carries responsibility. When trends joke about ‘resetting’ queer people, when audiences cheer it on, they are not being edgy. They are participating in a long tradition of silencing, correcting, and disciplining bodies that refuse to conform.

This trend reveals something deeper than ignorance or poor humor: it exposes how quickly societal norms can slip back into policing identities we fought to affirm. What is framed as a joke is really a rehearsal of erasure, replayed for likes and shares. If we continue to accept these narratives without question, we are complicit in perpetuating a culture that allows bigotry to resurface disguised as entertainment.

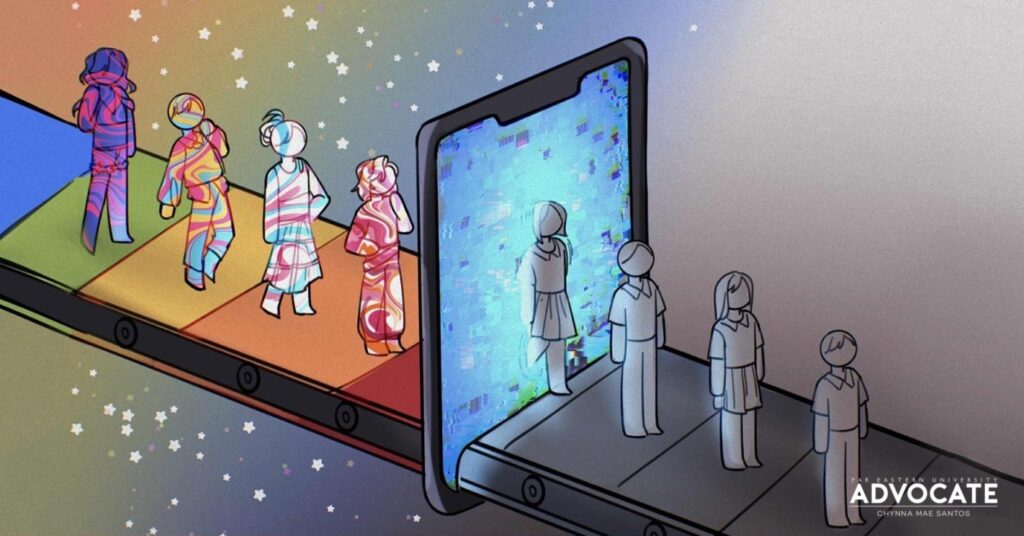

(Illustration by Chynna Mae Santos/FEU Advocate)